In a nutshell, this is how I got my agent. I emailed Debbie Golvan a query letter, got up and made a cup of tea, came back to my laptop and there, in my inbox, was a response. The best kind, requesting that I send through the first three chapters. Seven minutes it took her to respond. Just seven minutes. Surely this was some kind of sign?

More emails followed, a request for the full manuscript while she jetted about overseas, conversations that led to me tweaking the ending, and then the official offer to represent my novel. All this took a little over seven weeks.

There’s a prequel to this story which is terribly complex, but I’ll leave that for another day. For now the manuscript has gone out to publishers and the terrible waiting begins.

The path to getting an agent is so incredibly varied; everyone has a different story. So I thought I’d fill that terrible waiting space by asking three authors — Carmel Bird, Katherine Collette and Nick Earls — how they got their agents. Sure enough, their experiences were vastly different.

I’ve enjoyed reading these so much that I think this might have to become a series. But for now, let’s kick things off with Carmel.

Carmel Bird

This is a sweet story of destiny, in seven steps.

One: I didn’t have an agent. Ages ago an ex-student of mine said she had just engaged an agent whose surname was the same as mine, and furthermore this agent lived in my small country town. I had not heard of this neighbouring agent, and I made no attempt to find her.

Two: In February 2018 I gave a writing workshop at the Faber Academy. One of the students said her novel was being published the following week, and that she had a wonderful agent who shared my surname and village. I still didn’t wake up.

Three: Another student in the workshop said he was giving his manuscript to his agent (a different one) the following Monday. Then he said she would have response from publishers within a month.

Four: Now something about that ‘month’ really got to me. I am sure the student was exaggerating about the speed of response, but as I sat on the train going home, the three points above came together and said ‘agent, agent, agent’. Shazam!

Five: I went to the website of Sally Bird, Calidris Agency, and we had a meeting, and we realised we lived within five minutes of each other, and, even more important, that we could work with each other. It is a strange relief to me to feel that a professional and widely experienced agent is now going to present my work to publishers.

Six: As well as having a business relationship, we enjoy each other’s company. ‘Bird’ is my married name, and also Sally’s married name. We have discussed the fashionable idea of having hyphenated surnames: Sally White-Bird and Carmel Power-Bird. How mad would that be? I began here by saying this was a sweet story of destiny – I am wary of events that seem to be working in sync with destiny, but I think I resisted this little series of steps for long enough. I’m glad I gave in in the end. A five-minute walk can do you the world of good.

Seven: Sally is now representing my new novel Field of Poppies. I am so confident and delighted about all this.

Carmel Bird’s novels have been shortlisted three times for the Miles Franklin, and in 2016 she received the Patrick White Literary Award. Visit her at www.carmelbird.com

Katherine Collette

Recently, I interviewed my agent, Jacinta di Mase for a podcast I’m doing with a friend, the author Kate Mildenhall. I sent Jacinta the questions a week before the interview, and she came early to the studios. While the tech crew set up, Jacinta pointed to the bit where I summarised how we met. ‘We better get our stories straight,’ she said. ‘Because I don’t remember this how you do.’

The bit Jacinta didn’t remember, where we differed in our recollections, was that in my mind, she rejected my manuscript twelve months prior to signing me. In her mind, she said maybe, and asked me to re-submit.

So this is my version of what happened.

In 2016, I had a finished manuscript of my novel, The Helpline. At the time, Jacinta di Mase was president of the Australian Literary Agents Association (ALAA) and top of my list of prospective agents. I sent her an email describing the book and then tried to forget about it. They say if you haven’t heard after twelve weeks then the answer’s no. But surprisingly, she responded quickly, saying she’d love to read it.

I bundled it off, in electronic form. Two weeks passed slowly, and then she called. It was a polite Thanks but no thanks (I think).

I was upset, of course. I sent it to other agents on the ALAA website, but none of them were interested either. So I put in a drawer.

Flash forward six months and I was picked for the ACT Writers Centre’s Hardcopy program. Hardcopy runs across three weekends. The first involves workshopping, and the second is a serious of presentations from a range of industry insiders, including agents.

Jacinta was there. After her talk she stayed on for morning tea. While she drank her coffee, I angsted about going to talk to her.

Dear reader, I did not want to talk to her. It was only the sense that if I didn’t I’d be disappointed in myself that made me do it.

I’d like to say I was impressive, charming, thoughtful (etc.) but I wasn’t. It counts among moments I cringe at remembering. I was… not articulate. But she remembered the book and gave me some feedback, which I incorporated into the revised work.

We met again a couple of months later at the third round of the Hardcopy program, where participants have one-on-one meetings with ten different publishers and agents, all of whom have read the first thirty pages of your manuscript.

Given Jacinta had already rejected the work I wasn’t very optimistic about seeing her. What would we even talk about? She’d already said no. But that meeting counts as among the highlights of my writing career so far. Not only did she end up signing me, but she went on to secure me a two-book deal with Text Publishing.

In our recent podcast interview, I said to Jacinta, ‘We’re so often told that you get one bite of the apple, only one chance with a publisher or an agent. Yet, with you I had two.’

But again, she had a different take. ‘You always get second chance,’ she said. ‘It’s never really over.’

Insofar as there’s a moral to this story, that’s my take home message. It’s never really over, you always get a second chance.

Katherine Collette’s first novel The Helpline comes out in Australia in September 2018 (Text Publishing), and in North America (Touchstone), the UK (S&S) and Italy (Garzanti) in 2019. Visit her at www.katherinecollette.com

Nick Earls

I got my agent at a time when I really needed one, and through the generosity of a friend. It was 1994, and Brisbane still felt at more than arms’ length from the world of Australian publishing. I had toiled away at my writing throughout the 1980s in something of a vacuum. In 1989, I met Laurie Muller from UQP, and that eventually led to my first book (Passion, a collection of short stories) being published by UQP in 1992. But the critics mauled it, it didn’t sell, UQP rejected my next novel manuscript (or two) and I needed a fresh start.

Veny Armanno was back in Brisbane by then, and our first books had been launched together in 1992. By 1994, he was doing everything right. Jane Palfreyman was a gun young publisher and she’d signed him up to Picador and he was putting out novels. I was in a hole. Fiona Inglis had just left an editing job to join Tim Curnow at Curtis Brown and Veny was one of her first clients. My CV included a book that had tanked and some rejected manuscripts but, despite that, he pitched me to her. I sent Passion and some newer material, and she said she’d meet me. I either went to Sydney to do that, or happened to be going there anyway (despite the ridiculous early nineties airfare it would have involved, this meeting was the ultimate big deal for a writer who had wanted a break since 1978, so I would have paid if necessary). We talked. I liked her. At the end of our conversation she handed me a pamphlet about Curtis Brown and discussed their commission structure, etc. I was still anxious that this was an illusion, or that everyone got this conversation and then, ninety-nine per cent of the time it ended with her saying, ‘But that’s for other people. We won’t be signing you.’ I’d become far too conditioned to rejection. She led me to the door. She hadn’t rejected me, yet. I still had the pamphlet. Maybe I was actually about to get an agent? But I had to hear her say it. I said, ‘Does this mean you’re actually taking me on?’ And she said, ‘Oh, yes, sorry, didn’t I say that?’

Then I just needed to write something she could sell. From my multiple piles of possible novel ideas, instead of picking something I thought would best showcase my towering intellect, I decided to pick two that people might actually want to read. They ended up as After January and Zigzag Street. With After January, my connection with UQP was part of that working out, but with Zigzag Street the credit goes to Fiona. The manuscript missed out in the Vogel, but she knew Laura Paterson had just joined Transworld to set up an Australian fiction list, and that she was coming to a reading I was doing. Fiona did the groundwork beforehand, Laura liked what she heard, and off things went from there.

When Fiona went on parental leave maybe fifteen years ago, her assistant, Pippa Masson (who had been managing my diary), acted as my agent. When Fiona came back, it was clear Pippa was never going back to being an assistant, and she’s been my agent since then. It remains an important relationship, for a number of reasons. She knows me, knows my career and I trust her judgment. Also, I have a network of other agents too, but she’s the hub of that wheel. Through Cutis Brown, I have worked with literary agents in New York and London and, through a copy of Zigzag Street being shared around in LA in 1997, I have a film agent there. I also work with booking agents for events. But everything ultimately funnels back through Curtis Brown, where Pippa manages the bigger deals for me and Caitlan Cooper-Trent manages my diary.

‘The writing you needs to be passionate about your work, the business you needs to be as cold-hearted as an assassin’

When I was starting, there were fewer agents and I had no clue. I was too far from the publishing industry and there was no way to connect. Now distance isn’t what it was and the industry isn’t what it was either. It’s both more developed and a bit more desperate. If I were starting now, I’d definitely be trying to hook an agent, and fortunately there are quite a few good ones around. Having Fiona as my agent in the early days allowed me to focus on the writing while she — someone way more connected than I was — was there to keep putting my manuscripts in the right hands until something stuck. What I need now is different, but that’s what I’m getting from Pippa and Caitlan. I need someone to handle complicated things like film and TV contracts (sure, most of them go nowhere, but you need the paperwork right, just in case), to connect me internationally, to ask for more money than I’d dare to, to act as a sounding board and to provide me with industry intel while I sit here in Brisbane instead of turning up to events in Sydney or Melbourne night after night.

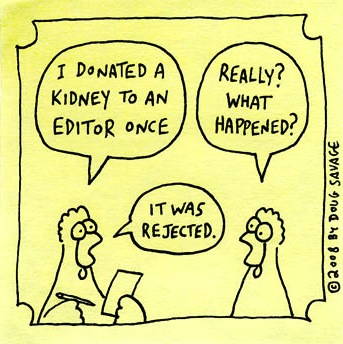

When trying to hook an agent, I think the key thing is to pitch yourself to them on their terms, as well as you possibly can, and then look away. Focus on something else while your work slowly rises higher in their slush pile. You need to separate yourself into two versions of yourself — a writing you and a business you. The writing you needs to be passionate about your work, the business you needs to be as cold-hearted as an assassin. Spend most of your time writing the best stuff you can. Send your work out to your current preferred targets, expect rejection, and then send it out again. That applies to agents as much as it applies to publishing outlets. If you get useful feedback, take it. But try, to the extent you can, to detach emotionally from negative outcomes, because they’re the norm. If your year has twenty rejections and two acceptances, your CV is two lines longer, you have made progress and no one needs to know about the rejections.

If you’re writing to an agent and you’ve won or been shortlisted in anything notable, let them know. If you’ve got publishing interest, let them know. If through a competition or a mentoring program (or anything) you’ve connected with an established writer who likes what you’re doing, see if they’ll pitch you to their agent, or other agents they know. It’s no guarantee you’ll get signed, but it takes you out of the slush pile and says you’re someone worth paying attention to.

Nick Earls is the author of 26 books, including two that have been adapted into feature films and five that have become stage plays. His most recent work is the award-winning novella series Wisdom Tree. Visit him at https://nickearls.wordpress.com/

This month I have a complete set of Nick Earls’ Wisdom Tree novellas to give away! Described by The Australian as ‘one of the most ambitious fiction projects being undertaken in Australian publishing’, all five books have garnered the highest praise. (‘You can’t write better than this. It’s simply perfect’—Elizabeth Gilbert.) If you’d like to get your hands on this linked set of novellas, simply sign up to my newsletter before 6 pm Thursday 23 August (link to the right). Open to Australian residents only. Winner will be randomly generated. Good luck!