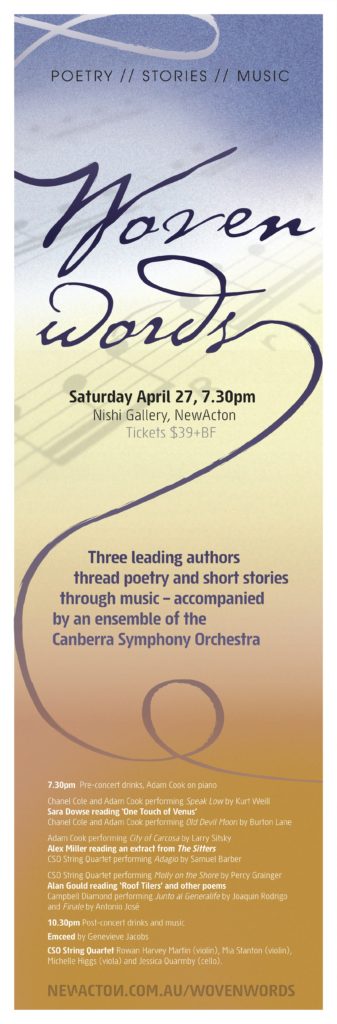

Whenever people talk to me about Woven Words the word ‘magic’ seems to crop up (read a review here). And I can’t help but agree that it was indeed a night on which magic happened.

You never quite know how an event is going to unfold. Woven Words was, in some ways, a grand experiment. An innovative idea driven by NewActon’s David Caffery, we couldn’t be sure if the event was going to soar or crash. I was pretty certain it was going to be spectacular, but in the end it was much more than that. If you’re lucky, an intangible connection — a synergy, if you will — happens between the artists and the audience. When it does, it’s electric. And it was.

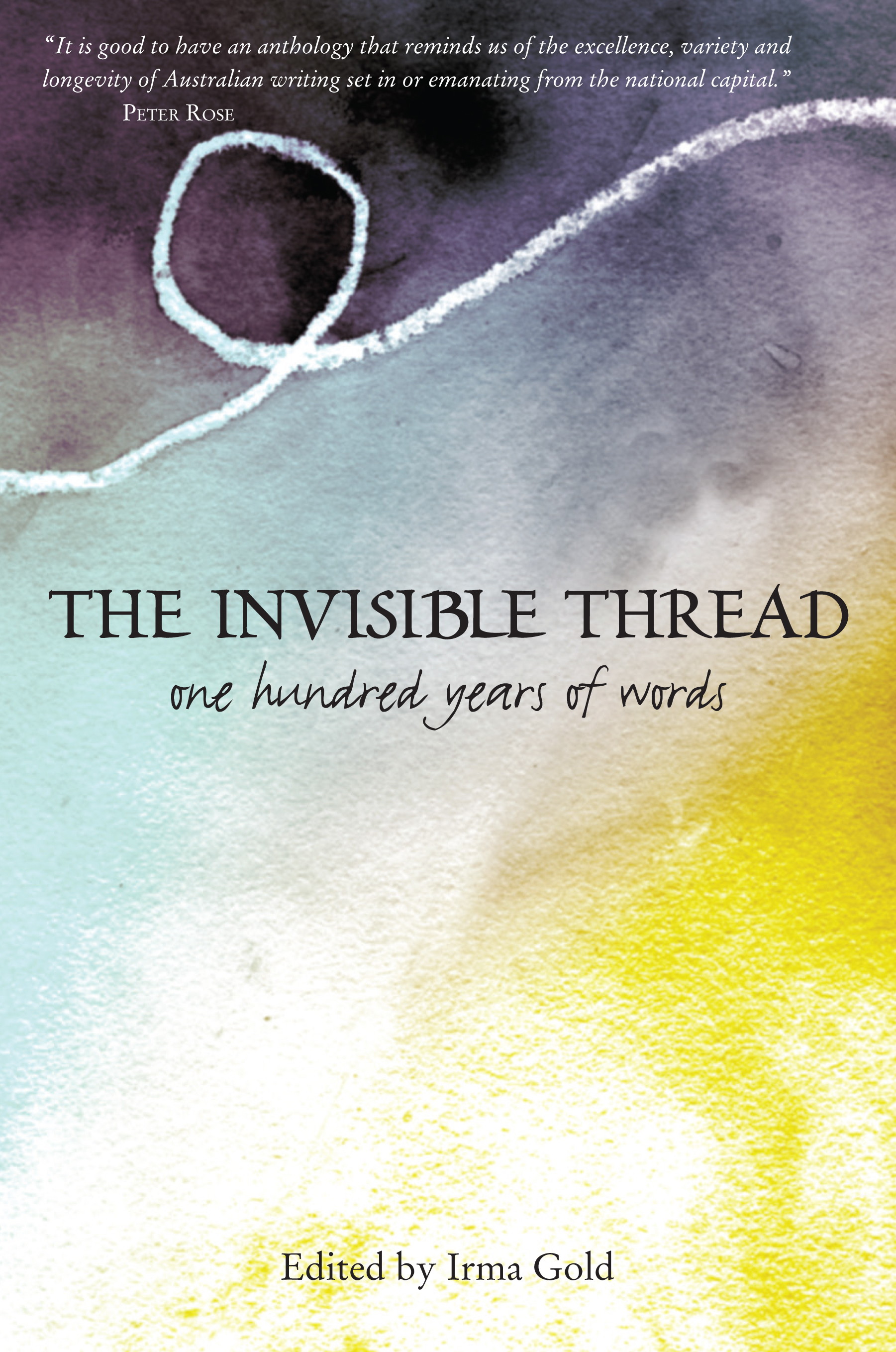

The evening kicked off with Sara Dowse reading from her Invisible Thread essay about a weekend spent with Hollywood movie star, Ava Gardner, when she was seven years old (you can read more about it in my interview with Sara here). This story captivated me all those months ago when I first read it, and it still draws me in every time. Hearing her read live was an absolute pleasure. She is a wise and gracious lady.

Sara and I have exchanged countless emails in the lead up to this event but I met her for the first time on Saturday. She was so much smaller than I expected (she commented that I was so much taller than she expected!). More importantly, she is an incredibly warm person with so many fascinating life stories to tell. I eagerly await her memoir which is currently in the works.

Sara chose two jazz standards to bookend her reading, ‘Speak Low’ from the movie One Touch of Venus, in which Ava Gardner starred, and ‘Old Devil Moon’ from the 1947 musical, Finian’s Rainbow. Chanel Cole performed both songs, accompanied by pianist Adam Cook. For those who aren’t aware, Chanel made it to the number five spot on Australian Idol in 2004 and since then has been gigging about town (as well as doing a million other things, as you do).

I’ve always wanted to see Chanel perform live but somehow never have. Her renditions were tender and full of grace. Sara whispered to me that they gave her goosebumps. Afterwards I got to spend a bit of time with Chanel as we ate olives and bread in the emptied out venue. Not only is she talented and beautiful but also incredibly sweet. Now I’m doubly a fan.

After each author’s section we took a break to absorb and reflect on what we had just experienced. Our host for the evening, Genevieve Jacobs from ABC 666, kept everything moving along with her usual finesse.

The middle section showcased Alex Miller reading from his novella The Sitters, extracted in The Invisible Thread. Alex has long been one of my favourite authors but I have only recently discovered that in person he has a biting wit. He can also imitate any English accent you’d care to throw at him, and is not afraid to speak his mind. I collected him from the airport on Saturday evening and over dinner he announced to the table that he could tell I had children because my car was a state. He should have seen it yesterday, I thought. Before his arrival my daughter had removed all the books and shoes and discarded items of clothing and vacuumed it thoroughly. It was as pristine as it will ever be. He did, however, claim it made him feel entirely at home given the (far worse) state of his grandchildrens’ car. As it turns out my daughter and his granddaughter share not only poor car etiquette but the same unusual first name.

Later that evening Alex managed to stir up the entire Woven Words audience by provocatively asserting that no one lives in Canberra by choice. Alex Miller, I’ve decided, is a wicked man, and I like him enormously. Hearing him read from The Sitters, I was spellbound. Alex recounted how his original draft of The Sitters was a 400-page tome, but on a long flight he ‘dreamt the book’. The voice of the story came to him and he knew exactly what he had to do. So he tossed the whole lot out and started from scratch. The result was the much tauter novella-length work that was published in 1995.

To bookend Alex’s reading Adam Cook performed ‘City of Carcosa’, the first movement from ‘Sonata No. 2’, written especially for him by composer Larry Sitsky, who is undoubtedly a genius in our midst. Adam’s performance of this technically challenging work was so powerful that I’m actually at a loss for what to say. As Alex Miller commented, it is not possible to truly comprehend or explain music — it speaks to our souls, moves us in ways that words cannot adequately express. Let me just say that I was witness to something extraordinary.

Then came Samuel Barber’s ‘Adagio for Strings’, composed in the year of Alex Miller’s birth, performed by the Canberra Symphony Orchestra (CSO) string quartet. Part of Barber’s ‘String Quartet Op. 11’, it is one of the most popular of all twentieth-century orchestral works. ‘Adagio for Strings’ is so sorrowful, so full of pathos, that I felt quite weepy listening to it (as photos from the night attest!).

In the last section Alan Gould read six poems that covered everything from the sea and sex to the staccato rhythms of flamenco-inspired poems. The latter two works presented plenty of breathing challenges but Alan pulled them off to great applause. Having worked closely with Alan as part of The Invisible Thread’s Advisory Committee, it was a particular joy to see him on stage. He is always such a lively and engaging performer of his work.

Alan selected ‘Molly on the Shore’ by Percy Grainger in response to his Invisible Thread poem, ‘Roof Tilers’ (you can watch Alan talking about this poem — and more — here). Some years ago I edited a book on Percy Grainger and I’ve always had a soft spot for him. Grainger wrote this work in 1907 as a birthday gift for his mother and it is a lively arrangement of two contrasting Irish reels. The CSO quartet’s performance was foot-tappingly good.

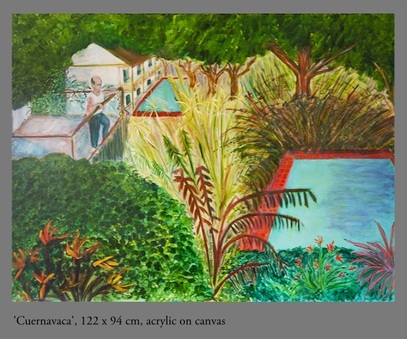

In response to Alan’s flamenco poems, guitarist Campbell Diamond performed two works, ‘Junto Al Generalife’ by Spanish composer Joaquin Rodrigo, and Finale, from the ‘Sonata’ for guitar by Antonio Jose. Rodrigo’s music counts among some of the most popular of the twentieth century, and the title of this work translates as ‘next to the Generalife’, the gardens surrounding the great Alhambra palace. The ‘Sonata’ is Jose’s most famous work and is regarded as one of the most technically challenging and conceptually profound works in the guitar repertory. I adore flamenco dance and music, so the dynamic interplay of Alan’s poetry and Campbell’s playing was, for me, a perfect note to end on.