Here’s a stat for you. On average Australian authors make just $12,900 a year. That figure is usually made up of a bunch of different income streams that might include teaching writing, festival appearances, PLR/ELR (if you don’t know what this is, read on), school visits, and a range of other writing-related activities. Book royalties often represent only a fraction of an author’s total income.

The market in Australia is small and consequently there is pressure on authors to sell enough copies of their book to warrant the publisher’s financial investment. Put simply, if a book doesn’t sell well enough, a publisher will think twice about taking on another book by that author. So if you love Australian writing, here are some ways that you can support authors and the industry that makes it possible for them to continue publishing.

- Buy their book, but know that all sales are not equal.

On every book sold authors make ten per cent of the RRP. So if the book retails for $30, the author makes $3. If the book has multiple authors, or an author and an illustrator, that ten per cent will be divided between them. So, for example, my picture book, Megumi and the Bear, retails for $27.95 which means that on every book sale I receive 5% or $1.40 (as does the illustrator, Craig Phillips). But this is only the case on full price sales. If the book is sold at a discounted rate the author may earn next to nothing. For example, on my latest royalty statement a bunch of Megumis were sold at discount, netting me the grand total of 13 cents per book. Deals like this are often done by the publisher when the book has been out for a while, but even a new release can receive just a few cents in royalties. How? you might ask.

Read More »Go ahead, make my day: supporting Australian authors

Well, here’s how it works. In order to get books into the major department stores (the Big Ws of the world) the publisher offers them at a drastically reduced cost. So if you purchase a book from, say, Kmart, you might get it a couple of dollars cheaper, but you’re also reducing the author’s already meagre earnings. And then there are all the online bookstores offering cheaper rates. Again, the author’s earnings are likely to be meagre. I’ve quoted Jo Case’s stark example before but it’s worth repeating here. Purchasing a copy of Case’s memoir, Boomer and Me, from an Australian bookshop meant she received $2.50 in royalties, but buying it via Book Depository UK meant only three cents in royalties.

Ultimately authors are going to be happy that you’re reading their book any which way, but if you can buy locally from a physical bookstore everybody wins.

- Better yet, pre-order the book

Pre-orders and first week sales are crucial for a book’s success. Pre-orders help determine the number of copies retailers will stock, and also help books hit the bestseller list. So if you’re intending to buy an author’s book when it comes out anyway, why not pre-order it to give them that extra boost.

- If you can’t buy their book, borrow it…

…but not from a mate, from the library. Most readers don’t know that at the end of every financial year Australian authors receive PLR (Public Lending Rights) and ELR (Education Lending Rights) payments based on the estimated number of copies held by Australian libraries. These funds are significant, and often exceed royalties on sales.

If you read anything like the quantity of books that I do, then buying every book is simply not possible. But when you borrow a book from a friend, or buy a copy secondhand, the author gets nothing. Supporting your local library is a better option. I regularly borrow books from the library and if I love the book I will often then buy myself a copy. A recent example is Lucy Treloar’s Salt Creek. I borrowed it from my local library and loved it so much that I bought a copy for myself, and have been buying it as a gift for friends ever since.

If your local library doesn’t have the book you’re after, you can request that they buy it. You’ll increase the author’s PLR payment and other library users will also benefit from your initiative.

- Write a Goodreads (or Amazon) review

I am a late adopter of pretty much everything, and Goodreads is no exception. I had an inactive account for years and have only just started actually using it (so come join me there!).

Reviewing and rating an author’s book does make a difference. The best kind of reviews give other readers a sense of what the book is about and why you enjoyed it. But if you don’t have time to construct a paragraph or two, a quick line — even just ‘loved this book’ — will always be welcomed. Aside from making the author extremely happy (and believe me it really does), the more reviews a book has, the more readers see it. And constructive conversation around a book is useful in generating awareness. I use the word ‘constructive’ because Goodreads can be a brutal place for an author. Many authors I know avoid it in order to maintain their own sanity. I think some reviewers forget that a real person with real feelings wrote the book that they are reviewing. So please be honest but kind.

- Tell your networks

If you’ve enjoyed a book let others know by tweeting, Facebooking or Instagraming about it. Even good old-fashioned face-to-face works a treat. Word of mouth is the best way to help a book make its mark because readers act on recommendations from people they know and trust. And the author will love you forever and ever.

- Write to them

It’s so easy these days to drop an author a line. Most authors are accessible via email, website contact forms and various social media platforms. And don’t underestimate the zing it will give your favourite author. You work so hard on any given book for so long in isolation and then when it goes out into the world you crave feedback from readers. As Roger McDonald once said ‘an author is a thirsting person in the desert’. Hand them that glass of water!

- Go to their events

Better yet, meet them in person. Get them to sign your book, tell them what you loved about their last one, even take a selfie with them! It’s the loveliest thing when someone comes up to you at an event and tells you how much they adored your book. Nothing beats it.

So there you have it. Six ways to make an author’s day.

In 2016, at the end of a solo three-week trip through Thailand, I was sitting on this bench at Kanchanaburi station when I began scrawling down a story in my notebook. Writers are always asked where their ideas come from and it’s the most difficult question to answer because, for me at least, they have complex and elusive origins. In this particular moment the motif of the train line struck me, but that’s as much as I can explain. Where the characters and their story came from I don’t know. But as Paul Murray says, ‘When the right idea comes along, it’s like falling in love.’ That’s how I felt with this story, even though my characters are falling out of love.

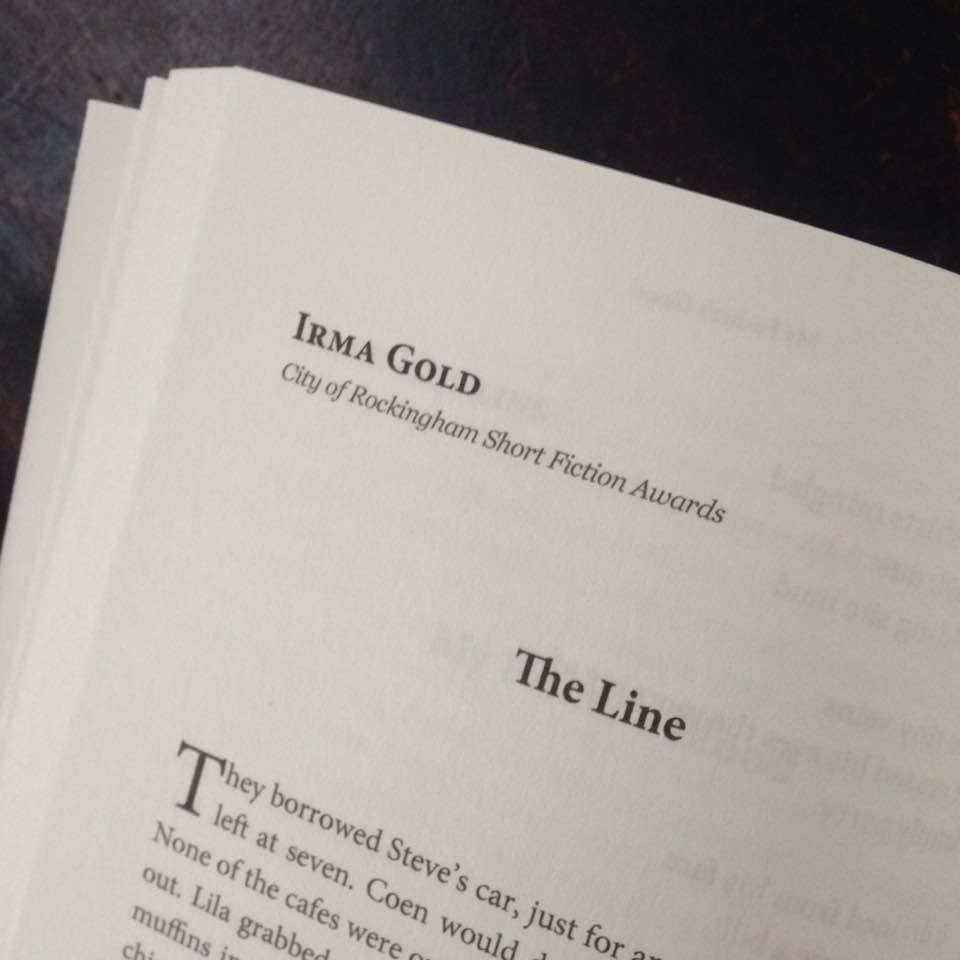

In 2016, at the end of a solo three-week trip through Thailand, I was sitting on this bench at Kanchanaburi station when I began scrawling down a story in my notebook. Writers are always asked where their ideas come from and it’s the most difficult question to answer because, for me at least, they have complex and elusive origins. In this particular moment the motif of the train line struck me, but that’s as much as I can explain. Where the characters and their story came from I don’t know. But as Paul Murray says, ‘When the right idea comes along, it’s like falling in love.’ That’s how I felt with this story, even though my characters are falling out of love. I tightened and edited the piece, by now called ‘The Line’, and gave it to my short story group who made helpful comments like ‘hope you didn’t have an affair as research’. (They may also have given some more useful feedback.) I rewrote the ending more times than I can count before I felt I’d struck just the right note. And then I sent the thing off to the City of Rockingham Short Fiction Awards. I rarely enter literary competitions these days, but the brilliant short story writer Laurie Steed was judging and there was a decent cash prize on offer. Needless to say I was thrilled when ‘The Line’ won.

I tightened and edited the piece, by now called ‘The Line’, and gave it to my short story group who made helpful comments like ‘hope you didn’t have an affair as research’. (They may also have given some more useful feedback.) I rewrote the ending more times than I can count before I felt I’d struck just the right note. And then I sent the thing off to the City of Rockingham Short Fiction Awards. I rarely enter literary competitions these days, but the brilliant short story writer Laurie Steed was judging and there was a decent cash prize on offer. Needless to say I was thrilled when ‘The Line’ won.