Judging a book by its cover

Let’s face it. No matter what anyone says, we do judge a book by its cover. Which is why the designer’s job is so important. As an editor I’ve been fortunate to work with some incredible book designers, and one of the very best is Sandy Cull.

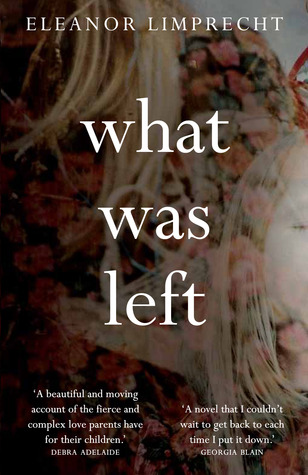

So often when I pick up a book because I’m struck by its incredible cover design, I turn to the imprint page and find Sandy’s name. Her work is striking and imaginative, clever and layered. Perhaps best of all, it’s obvious once you read the book that Sandy has understood what the author is trying to say.

Read More »Judging a book by its cover

Luckily for us, Sandy allowed me to throw a bunch of questions at her and take us inside her creative process.

Irma Gold: What led you to book design?

Sandy Cull: I completed a graphic design course and spent several years working in design studios, advertising agencies and then, when I lived in London for four years, magazine publishing.

Once back in Oz, I began freelancing for various magazines in Sydney before art directing a craft magazine for a few years. Wanting to return to Melbourne, a friend told me about a position for a designer at Penguin. It was love at first sight.

IG: What does a typical day, or week look like for you?

SC: I share a studio space with four designers, two photographers and four animation producers. I cycle either to or from the studio four days a week.

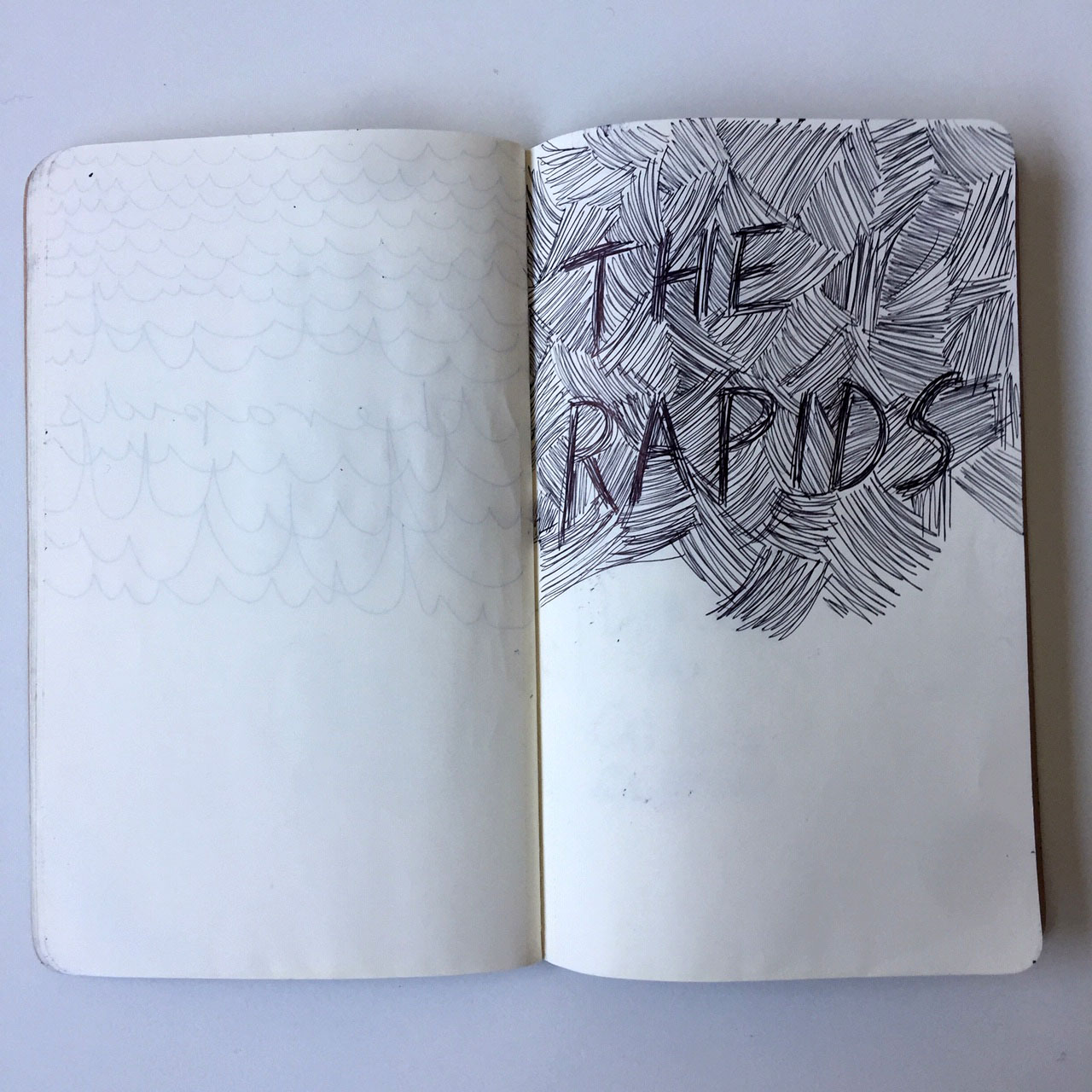

Every day I have at least one deadline, but often there are several things on my to-do list. It could be first cover roughs for a nonfiction book, text design for a fiction book, or time allocated for picture searching or photography, painting some hand type or scouting for props to shoot.

I do a lot of my reading on the train and at night, or on extended holidays. As a freelancer, I don’t tend to have many client/author/publisher meetings. Most communication is by email. Publishers make contact when they have a project in mind for me. If I can fit it into my calendar, I usually say ‘yes’.