words and wanderlust

I have a small problem. I am a travel junkie and a voracious reader. Combine the two and the result is an endless itch to jump on a plane.

I recently read Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts and was overtaken once again with the desire to visit India that first gripped me after reading Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. Not because I want to join the violent Mumbai underworld that Roberts explores of course, but because the writing so vividly evoked the place and its people. It brought alive the sounds and smells and vibrancy and colour of a country. It made me want to explore it for myself.

I recently read Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts and was overtaken once again with the desire to visit India that first gripped me after reading Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. Not because I want to join the violent Mumbai underworld that Roberts explores of course, but because the writing so vividly evoked the place and its people. It brought alive the sounds and smells and vibrancy and colour of a country. It made me want to explore it for myself.

Read More »words and wanderlust

For me, fiction does this better than any other form. On the Road by Jack Kerouac is perhaps the most well-known travel novel, but I have also been to Nigeria with Teju Cole (Every Day is for the Thief), to Indonesia with Madelaine Dickie (Troppo), to Spain with Hemingway (The Sun Also Rises), to Cambodia with Laura Jean Mckay (Holiday in Cambodia), and to Columbia with Gabriel García Márquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude). The list is long, and I could go on and on, but you see what I mean. Books can be grand adventures.

For me, fiction does this better than any other form. On the Road by Jack Kerouac is perhaps the most well-known travel novel, but I have also been to Nigeria with Teju Cole (Every Day is for the Thief), to Indonesia with Madelaine Dickie (Troppo), to Spain with Hemingway (The Sun Also Rises), to Cambodia with Laura Jean Mckay (Holiday in Cambodia), and to Columbia with Gabriel García Márquez (One Hundred Years of Solitude). The list is long, and I could go on and on, but you see what I mean. Books can be grand adventures.

Later this year I’m headed to South Africa, and not just through the pages of a book. As the birthplace of my father, it has long held a fascination. I explored Tanzania and Kenya in my early twenties, but it has taken me more than two decades to finally make it to South Africa. Let’s just say anticipation levels are pretty high. I’m hoping that I will find the spark of a novel there, but at the very least I know I’ll find a short story or two.

For me, travel is always entwined with reading and writing. In 2015, an artsACT grant sent me to Thailand as research for a children’s picture book. I returned not just with a finished manuscript, Seree’s Story (forthcoming from Walker Books), but also the seed of an adult novel. In early 2016, this time thanks to a CAPO grant, I returned to Thailand to undertake the research for that book. While in Kanchanaburi I read Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North, based on the Thai–Burma death railway, perhaps standing on the very spot where characters in his novel died, where real men died. Needless to say, it was a profound experience. After my return to Australia, I spent the rest of last year writing the first draft of my novel. Hopefully it will soon be ready to go on its own adventure out into the world.

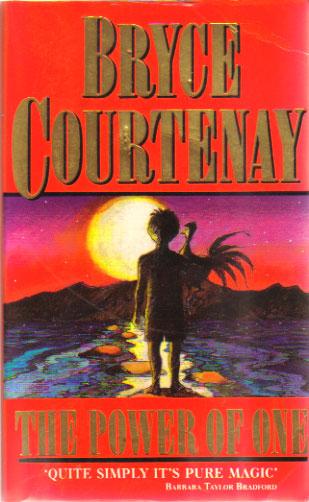

But back to South Africa, my next stop on this planet. I first fell in love with the country through fiction, as a teenager. I started with The Power of One by Bryce Courtenay, which has since sold over eight million copies. To my adult sensibility it is an idealistic, romanticised and overly sentimental representation of the struggles of apartheid, but at the time I fell in love with the hero, Peekay, and felt righteous indignation about the situation still facing Africans at that time. It led me to read my way through nonfiction about Mandela and Biko and Sobukwe. To fiction by Doris Lessing and J.M. Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer.

But back to South Africa, my next stop on this planet. I first fell in love with the country through fiction, as a teenager. I started with The Power of One by Bryce Courtenay, which has since sold over eight million copies. To my adult sensibility it is an idealistic, romanticised and overly sentimental representation of the struggles of apartheid, but at the time I fell in love with the hero, Peekay, and felt righteous indignation about the situation still facing Africans at that time. It led me to read my way through nonfiction about Mandela and Biko and Sobukwe. To fiction by Doris Lessing and J.M. Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer.

Last year I finally read Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country which had been on my To Read list for far too long. The novel subtly explores the tensions and issues that gave rise to apartheid. It reveals deep truths and creates empathy for multiple perspectives. This is what fiction has over nonfiction. We can walk around in characters’ shoes and see what they see, feel what they feel.

Now I intend to explore the fiction of South Africa in greater depth. I picked up the Granta Book of the African Short Story as a starting point and have discovered a new generation of writers whose novels I am rounding up. I’m travelling into the complexities of the place, while curled up in bed with a cup of tea. But come September I’ll be avoiding tourist trails and attempting to go beneath the surface, hoping to connect with the heart of the place and its people.

Like pretty much every writer except J.K. Rowling, I am not flush with cash. This means I must ration my travel. But while my feet remain firmly in Australia, there are novels to transport me. Even if they make me want to scratch that itch harder.

This post first appeared on Noted Festival’s blog here.