In the middle of the Serengeti the scrubby land is flat, stretching into the unbroken distance on all sides. We set up camp — a motley group of Americans, Germans, Brits and Aussies — and begin preparing the evening meal. The area is seemingly uninhabited, but suddenly children are emerging from everywhere. We peel vegetables, cut off the unwanted sections, and remove the fat from a pile of chicken. Discard the bits we don’t want. The children can’t believe how wasteful we are, are wide-eyed over it. We bag up our ‘rubbish’ — feeling a mix of emotions, the most prominent being multi-layered guilt — and hand it to the children, along with a bunch of much-coveted pens. They will take these stubs of carrot and onion and chicken fat to their mothers who will no doubt cook it into stews and laugh about the crazy foreigners who throw good food away. The following morning they will return with a branch of bananas and sticks of sugar cane as thanks for our generosity. The guilt is never-ending.

I am remembering this moment reading Cate Kennedy’s travelogue, Sing, and Don’t Cry, about her two years in Mexico. A different culture with the same Third World problems. For eight years I have wanted to read this book. When it was first released I stood in Borders and read the first paragraph of the first chapter:

I am remembering this moment reading Cate Kennedy’s travelogue, Sing, and Don’t Cry, about her two years in Mexico. A different culture with the same Third World problems. For eight years I have wanted to read this book. When it was first released I stood in Borders and read the first paragraph of the first chapter:

Our plane descends into Mexico City and we are ejected from it like goldfish out of a bowl, our mouths opening and closing as we try to gulp in enough oxygen in the high-altitude air. Stumbling jetlagged from the airport, we’re still trying to breathe as we take a taxi into a city where, legend has it, the pollution is so bad sparrows fall dead from the air.

Read More »Sing, and Don’t Cry

I was hooked. I stood there, holding its embossed cover in my hands, agonising over whether I could afford to buy it. I couldn’t. At the time we were — by First World standards — totally broke. I put it back, picked it up again. Could our budget stretch by thirty dollars just this once? I debated with myself. I placed it back, left the shop, returned. A ridiculous dance I hoped no one was observing. Eventually I left again, empty-handed.

Years later I regretted my decision when, no longer broke, I couldn’t find the book anywhere, even online where it seemed to be permanently out of stock. Every now and again, in my trawling of second-hand bookstores, I’d search for it without any luck. Until recently when I was in my local independent and asked, on the off-chance, if they had it in stock. No, they didn’t, but they could order it in. Bingo! Why hadn’t I done this before?

In Sing, and Don’t Cry Cate writes about the poverty and beauty of Mexico so vividly. She finds herself in this particular place, assisting with a rural microcredit project, after signing up for Australian Volunteers Abroad. Like all Cate’s writing (disclosure: I am a massive fan) Sing, and Don’t Cry is evocative and beautifully crafted. Every sentence is a pleasure to read.

But if you’re looking for a conventional travel account, this is not it. Sing, and Don’t Cry is as much, if not more, about Cate’s interior landscape as it is about the Mexican landscape, a place where her privileged Western value system is called into question. We are prompted to ponder ‘who is truly poor’ and, on her return to Australia, we witness Cate’s frustration and disillusionment with the superficiality of her own society.

Perhaps it seems odd that a book about Mexico has made me yearn for Africa — a place I fell desperately in love with many years ago — but I felt an affinity with her interior experience. As in Cate’s Mexico, in the two African countries I spent time in people had little but never complained, were always laughing. Every day I experienced the true meaning of the phrase joie de vivre. As much as I love my home, I can’t say the same about life in Australia. Cate reflects on the ugly self-absorption of our resource-rich Western world where we feel justified in complaining about the smallest of irritations. First World Problems, we say, and laugh, recognising how ridiculous we are. And yet we continue.

I remember returning from Tanzania to London, where I was living at the time. The complete disorientation of it. A country where people have everything and yet laugh sparingly. Where even the weather is incapable of enjoying itself. On my second day back I went into a corner shop and handed the woman behind the counter a 33p chocolate bar. Before I caught myself, I tried to barter the price down. An instinctive habit. ‘Sorry,’ I said, laughing. ‘I’m just back from Tanzania.’ She frowned, said nothing.

And so you unravel. At first you feel you will never again take what you have for granted, complain about matters of inconsequence. But you slip — slowly, barely noticing, until you forget. You moan about a delayed train or a lukewarm coffee or the lack of shopping trolleys with unbroken child restraints.

Sing, and Don’t Cry reminded me. It was discomforting, and I am grateful.

This post was first published by Meanjin here as part of its What I’m Reading series.

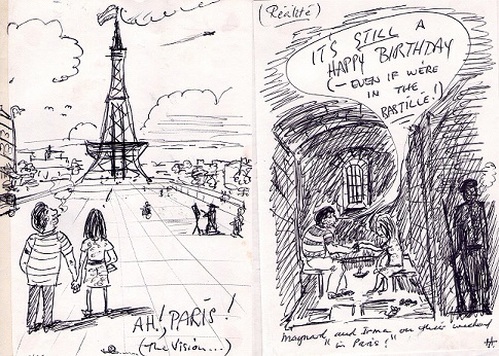

In 2016, at the end of a solo three-week trip through Thailand, I was sitting on this bench at Kanchanaburi station when I began scrawling down a story in my notebook. Writers are always asked where their ideas come from and it’s the most difficult question to answer because, for me at least, they have complex and elusive origins. In this particular moment the motif of the train line struck me, but that’s as much as I can explain. Where the characters and their story came from I don’t know. But as Paul Murray says, ‘When the right idea comes along, it’s like falling in love.’ That’s how I felt with this story, even though my characters are falling out of love.

In 2016, at the end of a solo three-week trip through Thailand, I was sitting on this bench at Kanchanaburi station when I began scrawling down a story in my notebook. Writers are always asked where their ideas come from and it’s the most difficult question to answer because, for me at least, they have complex and elusive origins. In this particular moment the motif of the train line struck me, but that’s as much as I can explain. Where the characters and their story came from I don’t know. But as Paul Murray says, ‘When the right idea comes along, it’s like falling in love.’ That’s how I felt with this story, even though my characters are falling out of love. I tightened and edited the piece, by now called ‘The Line’, and gave it to my short story group who made helpful comments like ‘hope you didn’t have an affair as research’. (They may also have given some more useful feedback.) I rewrote the ending more times than I can count before I felt I’d struck just the right note. And then I sent the thing off to the City of Rockingham Short Fiction Awards. I rarely enter literary competitions these days, but the brilliant short story writer Laurie Steed was judging and there was a decent cash prize on offer. Needless to say I was thrilled when ‘The Line’ won.

I tightened and edited the piece, by now called ‘The Line’, and gave it to my short story group who made helpful comments like ‘hope you didn’t have an affair as research’. (They may also have given some more useful feedback.) I rewrote the ending more times than I can count before I felt I’d struck just the right note. And then I sent the thing off to the City of Rockingham Short Fiction Awards. I rarely enter literary competitions these days, but the brilliant short story writer Laurie Steed was judging and there was a decent cash prize on offer. Needless to say I was thrilled when ‘The Line’ won.