Take four

‘I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood.’ Audre Lorde

This is what we writers do, in our private corners of solitude. We put words on the page that go out into the world and speak to readers. But a writer’s job also involves getting on a stage and speaking directly to those readers, trying to articulate the thinking behind the messy and elusive process of creating a work of fiction. It can be nerve-racking and exciting and stimulating. In the lead-up to an event I always feel anticipatory nerves, but once I’m on the stage I enjoy myself, and often come away feeling buoyant.

I’ve been part of four very varied events on writing and/or editing in recent weeks and I thought I’d share a little about the experience of each of them.

Most recently I was on an ‘Animal Rights Writing’ panel with Karen Viggers and Sam Vincent. I’ve never seen a panel programmed on this subject before. (Hit me up in the comments if you have, because it’s a topic I’d love to see discussed more.) This session was chaired by Nigel Featherstone who managed to expertly guide the discussion through our respective areas of interest. Our books deal with kangaroo culling (Karen, The Grass Castle), international whaling (Sam, Blood and Guts) and the exploitation of elephants for tourism (me, a children’s book, Seree’s Story, due out with Walker Books, and a work-in-progress novel, Rescuing Chang). Our conversation covered much ground, but, for me at least, the key idea that emerged was that conservation issues tend to be distilled into polarised positions which don’t necessarily reflect the complexities involved. Life is full of grey, and solutions are rarely of the black-and-white kind. Fortunately, writing can explore the grey. While this event delved into the darker side of humans’ impact on the world, it was a thoroughly stimulating and thought-provoking discussion. And as the icing on the cake, I returned home to an email from an audience member who felt moved to get in touch after hearing me speak about the devastating situation facing Asian elephants. With both my books yet to be released, I’m looking forward to many more conversations like this one.

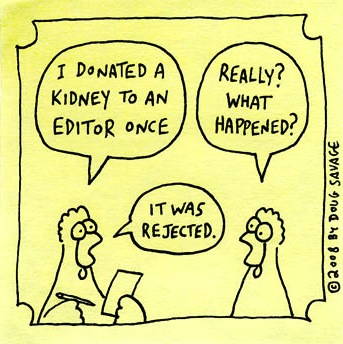

As part of Noted Festival, I was on a panel with Alan Vaarwerk (Kill Your Darlings) and Sian Campbell (Scum Magazine), ‘Literally the Worst: Bad Writing and Badder Editing’, with Homer Editor Ashley Thomson chairing. I wasn’t keen on the title’s negative angle, but I guess a feisty premise draws the crowds, and the event was certainly packed. Fortunately the focus of discussion was productive, emphasising ways for writers to improve their craft. We also spoke about the hallmarks of good editing and when to identify ‘bad’ editing. In particular, I spoke about the need for editors to work with the author’s voice, not impose their own. Our own idiom is always what sounds ‘right’, so good editors learn to recognise their own preferences and then set them aside. They essentially become chameleons, taking on the colours of the manuscript in order to help the author make their work the very best it can be. (As you can see,  Shauna O’Meara choose to illustrate this part of our conversation; my first time immortalised as a cartoon!) We spoke about a whole lot else besides and the event was podcasted here if you’d like to have a listen.

Shauna O’Meara choose to illustrate this part of our conversation; my first time immortalised as a cartoon!) We spoke about a whole lot else besides and the event was podcasted here if you’d like to have a listen.

For the next two events I was the one in the interviewer’s hot seat. It’s such a responsibility being the interviewer. Over the years I’ve seen the way poor interviewers give authors no place to go and leave everyone feeling flat, and conversely the way brilliant interviewers draw the very best out of their subjects, gleaning new insights. Part of the skill is developing a rapport with the interviewees before hitting the stage, which is of course easier if you already know them. It’s also important to be super prepared but then be able to go with the flow on the day, so that the conversation evolves, rather than rigidly following a pre-existing set of questions.

It’s such a privilege chatting with other writers, and the in-conversation event with Marion Halligan and John Stokes about their lives together was one of the loveliest events I’ve been a part of. Marion and John are perhaps best described as Canberra literary royalty. They are a warm, generous and supportive presence in the local community, and our discussion reflected that. There was much laughter, but also tears. Both have written so movingly about grief and loss, and John’s reading of his prose poem about the death of Marion’s daughter, ‘Funeral Address for a Stepdaughter’, had the audience reaching for the tissues. Marion once wrote, ‘Grief does not dissipate, it is something that exists, and must be valued, even treasured.’ Wise words indeed. It was a rich and wonderful hour spent with two marvellous writers.

And finally, I interviewed Robyn Cadwallader about her stunning debut novel, The Anchoress, as part of Festival Muse. I wrote about some of our discussion here, so I won’t rehash it, but Robyn was a delight to interview—thoughtful, insightful and intelligent. Our discussion lingered in my mind long after the event was over.

And finally, I interviewed Robyn Cadwallader about her stunning debut novel, The Anchoress, as part of Festival Muse. I wrote about some of our discussion here, so I won’t rehash it, but Robyn was a delight to interview—thoughtful, insightful and intelligent. Our discussion lingered in my mind long after the event was over.

Next up, I’m heading to Holy Trinity Primary School in my role as Ambassador for the ACT Chief Minister’s Reading Challenge. School visits are always heaps of fun, so I can’t wait to meet all those new little readers.