The third Canberra Writers Festival has just wrapped, and this year I found more to love on the program than in previous years. In fact I wish I’d been able to split myself in two for several timeslots. If you’re after rundowns on lots of the sessions, head over to the Whispering Gums blog, but I thought I’d just highlight a few of my favourite events here.

First up though, I was on a Canberra Writers Festival preview event with journalist Sam Vincent, moderated by the Conservation Council’s Larry O’Loughlin. We spoke about animals in literature, and the power of words to change the world. Interestingly, this theme was echoed throughout the festival in many different ways. But in this session I naturally spoke about the animal rights issues involving elephants in Asia, which relates to my next book. I could talk about the complexity of these issues for days, but in truth I don’t recall the conversation in enough detail to recount it here (events are always a bit of a blur afterwards). I do remember that it was a thoroughly enjoyable conversation with some thoughtful and intelligent questions posed by the audience. Can’t ask for more than that.

But on to other sessions. The Prime Minister’s Literary Award Recipients session was moderated by the wonderful Sue Whiting, a children’s author and editor (formerly my editor at Walker Books) and one of the judges for the PMLAs. Her panel consisted of a diverse range of writers — children’s author Wendy Orr, historian Peter Cochrane and poet Anthony Lawrence — and yet she managed to make this a cohesive and interesting session. Ryan O’Neill was also billed as part of the panel, and I was looking forward to hearing him speak, but sadly he was unable to attend due to a death in the family.

It’s impossible to cover everything in this discussion so I’m going to touch on a couple of points that most interested me. The PMLAs are the richest Australian literary prize, with each author taking away $80,000 tax-free. The financial benefits for writers — most of whom are unable to live off royalties — are obvious, but Wendy recounted how the prize meant so much more to her.

Despite spending her whole adult life in Australia and writing all her books here, she has always been referred to as a Canadian author. She has repeatedly been told that she cannot say that Nim’s Island was the first Australian book to be made into a Hollywood film, because she’s ‘not Australian’. Naturally she found this deeply hurtful, but the PMLAs changed all that. ‘I can say I’m an Australian author now, and my books are Australian books.’ Bravo!

A question from the audience raised the contentious issue that the PMLAs are the only Australian award where a politician can overrule the decision of the judging panel. The Prime Minister has intervened on three occasions and in two of those cases the prize was shared between the judge’s choice and the PM’s choice. In 2014, Tony Abbott’s overruling of Steven Carroll’s A World of Other People to jointly award Richard Flanagan’s Narrow Road to the Deep North backfired on him spectacularly when Richard used the platform to criticise the government’s policy on refugees.

But on one occasion the judges’ choice, Frank Bongiorno’s The Sex Lives of Australians, was ‘completely red carded’ by Kevin Rudd and replaced with his choice of Ross McMullin’s Farewell, Dear People. Peter Cochrane spoke passionately about the need to change the award’s terms and conditions which allow the PM to undermine the judges at will. ‘It brings the award into ill repute,’ he said. ‘It’s feudal. If you’ve got an expert judging panel its finding should be final.’

But I want to give the last word to Wendy on the positive impact of the awards. ‘They get people talking about poetry and children’s literature and history which people don’t normally talk about.’ And that is definitely a good thing.

In a completely different vein was Majok Tulba’s conversation with Michael Fitzgerald about his most recent book, When Elephants Fight, which follows the bestselling Beneath the Darkening Sky. It tells the story of Juba who is forced to flee South Sudan’s civil war, hiking 700 kilometres through a jungle full of lions, scorpions and snakes to a refugee camp where life is a catalogue of horrors.

Both books are ‘seventy per cent autobiographical’ but Majok chose to write fiction because it ‘was safer’. ‘Everything that is happening [in South Sudan] they don’t want the world to know. And they hate people who talk about it,’ he explained. ‘So to say, ‘I know this guy and he has done A, B, C’ — that would have given me a lot of problems.’ But with fiction ‘they don’t worry. They say, ‘It is not about us.’’

Beneath the Darkening Sky was a difficult book to read. I kept imagining my own young boys being taken from me, handed a MK47 and ordered to kill people. It is difficult to comprehend. But Majok said that ‘what happened in real life is more horrifying than a horror movie. I had to leave the most horrific parts out … to make it digestible for the reader.’ He added that writing the books helped release him from his most terrifying memories. ‘They are trapped on paper. So it helped. It helped a lot.’

I’m sure When Elephants Fight will be an equally challenging read, but I’m up for the challenge. And despite his ordeals Majok was always sustained by hope. ‘Someone who gives up hope will never survive,’ he said. ‘When you give up, your life is over.’

When Majok eventually arrived in Australia in 2001 he experienced extreme disorientation. ‘I felt like I landed in a world that was out of this world. Everything was terrifying. Everyone looked the same.’ Growing up in South Sudan he had assumed everywhere in the world was in a constant state of war. ‘We’d seen movies like Rambo and Commando and we thought there was fighting everywhere. And when I came to Australia I realised that was not the case. And how people could live in harmony despite political differences.’ As ridiculous as the whole recent leadership spill has been, Majok put it in perspective. ‘If Canberra was South Sudan right now there would be tanks rolling in the streets.’

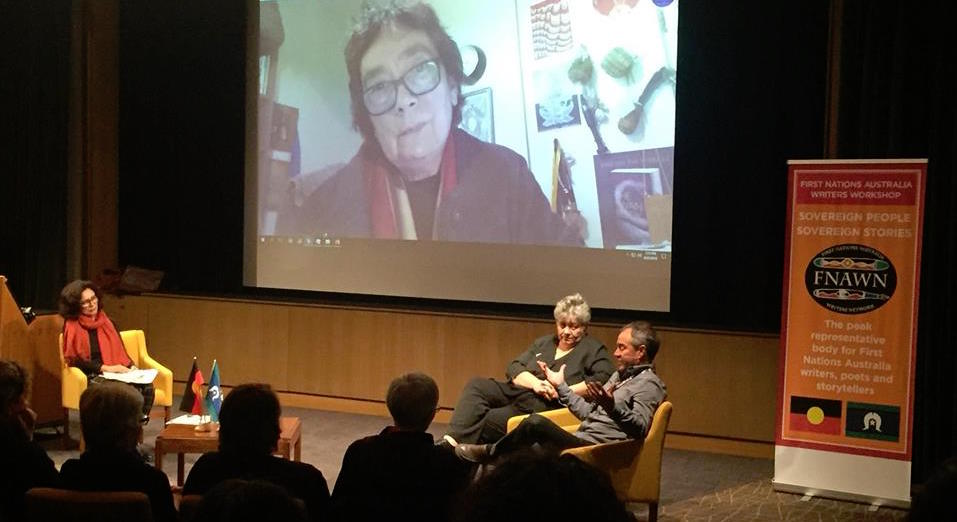

From Africa back to Australia, Saturday night saw a packed theatre at the National Library for An Evening with First Nations Australia Writers. It opened with four writers reading four poems each, with Ellen van Neervan the standout for me. This was followed by a panel with three of Australia’s greatest writers: Alexis Wright, Melissa Lucashenko and Kim Scott. The conversation had such depth and was so multilayered that I’m at a loss as to how to summarise it in any meaningful way. It felt as if it was built upon the weight of so many years of conversations, and it was a privilege to be in the room.

I will, however, relate the response to a question from the audience about how to be a good white ally. Kim suggested that it was important to ‘listen’ and Melissa said to ask yourself the question, ‘How will this benefit the local [Aboriginal] community?’ If it doesn’t, ‘think again’.

During the session Melissa also made a statement that really resonated with me, and I want to conclude with it. She said, ‘It is the job of any writer to pay attention. Tell the truth. Write towards power.’

Great summary Irma. I agree that it would have been good to be able to be in two places at once this year!

Lovely to see you and get a sneak peek of your next beautiful cover!

Great summary, Irma. I wish I could just do this!! Why do I have to regurgitate it all!

I hope to do the FNAWN event tonight – and had decided to frame it somehow around the “white ally” bit. It’s a critical issue. That audience question was close to the question I wanted to ask but she asked it so well.

Ha! I’ve taken the cheats way out. Yours is a much fuller representation of the sessions which is why I’ve handballed to you! I’m fascinated to see how you write up the First Nations evening. I agree, that question was so clearly articulated. And it’s so important to think carefully about how to be a good ally.